Author: Jessica Cushing

I have recently graduated with a BA (Hons) in Early Childhood in Society from the University of Worcester, and I am continuing my academic journey with an MSc in Psychology. As a mature student, a social pedagogy practitioner and parent of two children, there is a certain aspect of today’s society that I argue needs addressing across the multiple roles I have experienced in terms of interactions with children and young people.

Professionals worldwide can share knowledge, experience and research and even build professional relationships and multi-agency collaboration, whilst never being in the same room. Families can stay in regular contact over wide oceans and time zones, maintaining bonds and communication. What does this mean for children and their social world? And what does this mean for the practitioners working with them?

When homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic, I saw firsthand how technology and social restrictions impact children’s socialisation. My daughter, aged eight at the time restrictions began, struggled with the lack of time spent playing with friends at school and in the homes of friends and family. However, through the use of technology and social platforms such as Zoom and online games, her friendship group continued with play and communication in the virtual landscape. Relationships were reliant on the virtual interactions had through the internet and mobile phones in a time when accessing physical social interactions was not an option with social distance restrictions in place. Those children who did not have access to these virtual playscapes often communicated less with their peers. These children were isolated from pre-pandemic social circles and relationships due to the more traditional social interactions, such as parks, play dates and school playgrounds not being an option to counteract the unavailability of in-home technology use. The whole experience of relationships in a COVID-19 world showed how socialisation has the potential to look very different today compared to a time when children did not have access to technology.

The seed of an idea was planted in those pandemic experiences, and it began to grow as I learned more about Social Pedagogy during my study of the BA (Hons) Early Childhood in Society degree at the University of Worcester.

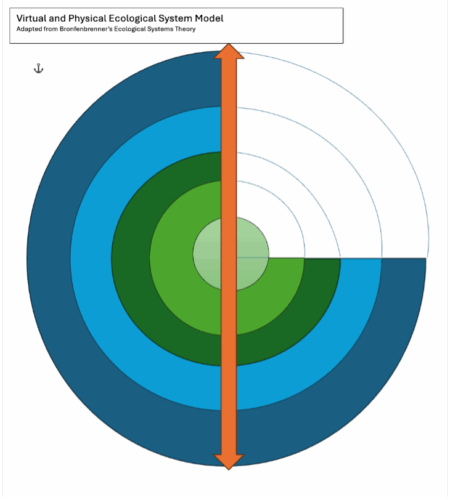

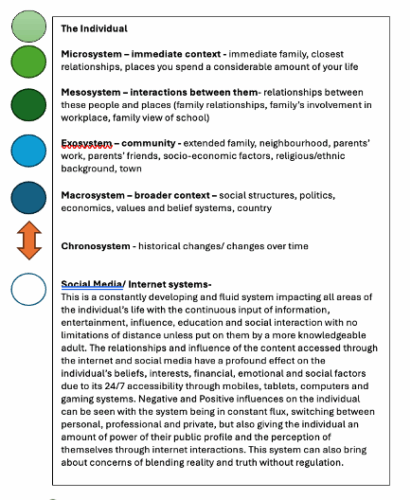

What it looks like for children and young people to move between the multilayered worlds of their virtual and physical relationships became clearer through experiencing placements and theorists’ ideas on discourses of childhood. Bronfenbrenner’s Bio-Ecological Systems Theory provided an aha moment for me as I recognised one social world which was missing in this model, but which plays a significant role in the lives of modern children.

In adapting Bronfenbrenner’s Bio-ecological Systems Theory, I hope to bring about a tool in which social pedagogues and practitioners working with children and families can work to answer the question, What might the life world orientation and social relationships of a young person look like in today’s society? The Virtual and Physical Ecological Systems Model (VPESM) shows how, depending on the child and their interaction with technology, the systems Bronfenbrenner first developed interact and change, bringing about different social connections, relationships and sharing of information/experiences in both the virtual and physical worlds. This means that each child’s VPESM would look different depending on the technology they use, how much they use it and with whom they interact through it. A baby, for example, would have minimal virtual systems due to their lack of direct use with technology. However, it could be argued that they would still have the need for virtual systems due to parental use of screens and the internet to connect with family, such as photos or video calls involving the baby. In comparison, a teenage child’s VPESM would contain larger, more widespread virtual systems in their use of technology in aspects such a learning, socialisation and online play. Unlike a baby, older children would have more autonomy over what they share, access, or how they interact with others within their use of technology and the internet.

Alongside this question, it is my hope that in having an understanding of children and young people’s use of the internet and virtual spaces they are a part of, adults and practitioners working with them can have a better understanding of how this impacts their wellbeing, social development and learning. In my experience working in classrooms with children between the ages of 7-11 years, I have seen a gap in understanding what children are interested in or what is trending in children’s online feed, games and social media. This was seen when children in settings were stimming, vocalising or discussing memes seen through their use of social media. Practitioners were unaware of the context of these vocalisations or online content until it was pointed out by another child or adult at the time.

In an ever more complex and changing online social landscape, there is a growing need for practitioners to have their own understanding of what is trending and viewed by children.

Practitioners who have a professional curiosity about modern childhood social contexts, virtually and physically, stand to have a profound effect on how they can build relationships and understanding of the child’s social circles in the fluctuating experience of being a young person in a technology-oriented world.

Additionally, whilst putting together the VPESM whilst working on my final assignments at university, I was working on a module focusing on children’s play and what that looks like. It became apparent that the model could be used to understand play in the virtual and physical playscapes that children access. This is an avenue I would like to consider in the future, as I see it bringing opportunity for discussion with other social pedagogues.

As I continue to refine the model, I’m keen to open up conversations with fellow social pedagogues: How might this framework be applied in broader practice with children, families, and communities? What possibilities or limitations do you see? I warmly welcome any reflections, feedback, or critical engagement with the model at this early stage of its development.

As someone who is only beginning my academic and professional journey into social pedagogy. I’m excited by the possibilities that dialogue and shared thinking can bring. Thank you for engaging.

If you would like to be put in contact with Jessica to engage further, please email info@sppa-uk.org.