By Jameel Hadi

Every child is an explorer, blessed with the urge to wanderlust. Show the child various ways of navigation, weather-sense, boat-building and sailing. Help the child build a small shipping vessel and test it together to the open sea. Teach him how to fish. Now, let the shipping vessel start its journey to the uncharted waters of life. The child is the captain of the ship and you are just a companion to the child’s journey, as a physical presence, a pleasant memory or a soothing voice inside his heart. It’s the child’s choice not yours. Enjoy and treasure every moment of it. Vasileios Tiliakos, International Rescue Committee’s (IRC), Senior Child Protection Manager for Greece.

In the UK, young unaccompanied asylum seekers and refugees life’s are preoccupied with worries. These include their legal status, benefits, housing and education. Surviving to Thriving supported by the Red Cross and My Bright Kite, led by Gulwali Passarlay , have responded by connecting young asylum seekers and refugees with activities and their peers.

In a Safe Zone in Alexandria, Greece, home to 30 unaccompanied boys, you get a palpable sense that the young people are living as young people should: in the moment, while playing a role in creating their futures. This is a result of the emphasis on everyday activities and the Common Third (see below).

The numbers of unaccompanied children in Greece are rising; latest figures estimate this total to be 3790. This includes an increasing number of children from Pakistan, who make up 40% of this total. Legal definitions of refugee status fail to address challenges of contemporary childhood. Increasingly children are bearing the brunt of the world economic crisis and impact of inequality.

Greek families are no strangers to moving country in search of a better life. Vasileios Tiliakos, the International Rescue Committee’s (IRC) Senior Child Protection Manager for Greece argues that the influx of refugees and migrants is no longer a ‘humanitarian crisis’ but an opportunity to revitalise the country. He points out Greece has a long tradition of immigration and migration and that new residents can replenish the younger generation, many of whom have left to seek employment in other countries.

The Safe Zone in Alexandria is one of ten in Greece established by NGO’s within refugee camps as an alternative to police detention, housing boys aged between 14 and 17 years. Here, the thirty boys, originated from Iraq, Libya, Syria, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan.

The accommodation is an austere converted container with five shared bedrooms and communal bathrooms, kitchen and living room. The term ‘boys’ used by staff, rather than asylum seeker, refugee or service user, is deliberate, stressing the care and rights owed to these children. The boys receive legal advice, to enable them to decide whether to seek residency, return to their country or understand the implications of continuing their journey to meet up with family or friends.

The child protection team comprises social pedagogues, social workers, psychologists, cultural mediators, caretakers (akin to residential workers in the UK) and drivers, who act as assistant caretakers.

The term caretaker in Greece is instructive, it does not denote looking after property, but rather the emphasis is on providing care. The primary duty of all staff, including drivers, is to take responsibility for the upbringing of the boys. Boys participate with their care worker in the drafting of a best interest assessment. This assessment does not collate data about the situation that resulted in their journey or in addressing issues of status or residence. These are the boy’s personal stories and it is entirely up to them as to what they share. The emphasis is on the present and its relationship to their future aspirations. Links, between the boys and parents or other significant adults are maintained through skype.

The determination of best interests (article, 3 UNCRC) is a living process that involves the boys in making decisions (article, 12 UNCRC) about the ‘everyday’. The boy’s needs informs the work of the child protection team, rather than their legal status, minimum standards or risk. The Common Third creates a unified approach and environment to realise the above.

The Common Third is a practical approach to social pedagogy that originated in Denmark and expresses the connectedness between relationships and learning. In the Safe Zone in Alexandria, this means connecting the boys with the child protection team, each other and the wider community. Michael Husen explains that human connection requires the sharing of activities. He uses the example, that for a ‘party’ to be a celebration, those attending must have shared experiences with others.

Imagine that you have left your family and undertaken an arduous journey to a new country where you experience a multitude of anxieties including detention. This is something Vasileios describes as a dark tunnel. You move to a Safe Zone, then are throwntogether with a group of boys from different countries, in cramped conditions and receive instructions from people who to you, are officials representing authority. You may well be frightened and not know who to turn to or trust. In such a context, it is easier to form relationships, especially if you do not have a common language, if you share activities and mutual interests.

The sharing of activities creates an equal relationship between the worker and the child, one that views the child as resourceful in shaping their environment. Pat Petrie (2011) explains that the setting for social pedagogues provides a shared living space between children and staff.These relationships are not about therapy, problems or bureaucratic compliance. Rather she argues, everyday activities, be they informal (e.g., washing up), practical (fixing and repairing) or formal (sport) create meaning within relationships, the shared living space and beyond.

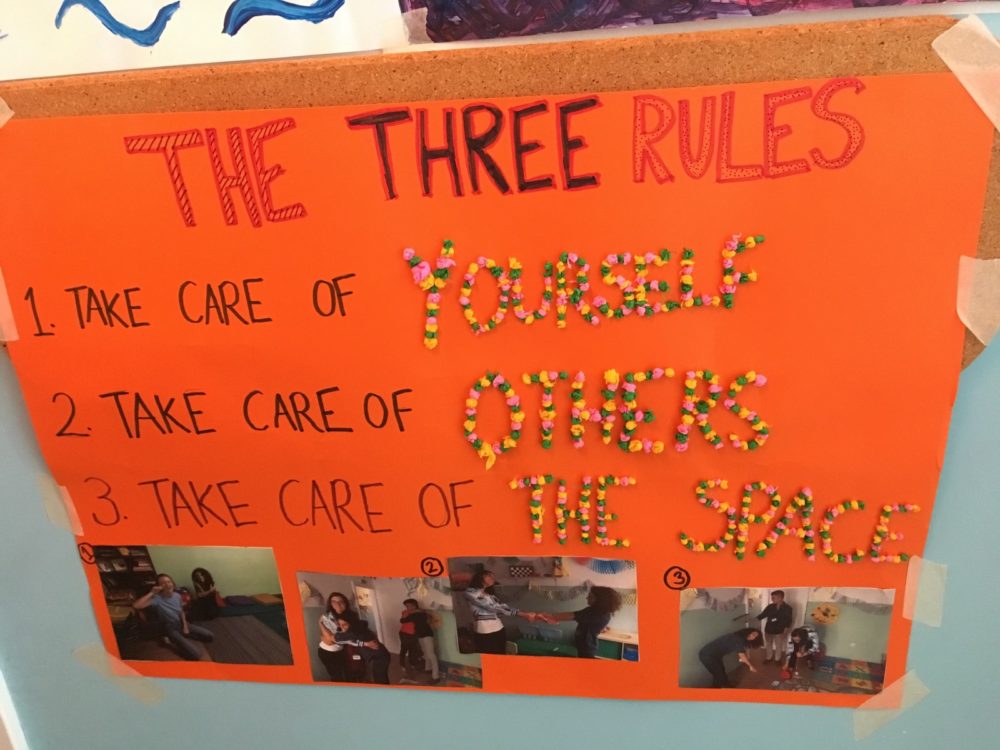

In the Safe Zone this process promotes inclusion and provides a unifying element between staff and boys. The everyday activities from cooking to attending language classes help to develop a culture of shared norms, values and rules based upon collaboration. This spirit of cooperation means that new boys are quickly welcomed and assimilated into the group. This explains the low levels of conflict and critical incidents reported within the Alexandria Safe Zone.

A weekly residence meeting addresses the agenda of the boy’s, not the organisation. The meeting I observed, contained much laughter and playful cynicism on the part of the boys and willingness by staff to address their requests. Their priorities are similar to young people everywhere and centred on leisure and recreation.

The meeting discussed, spices required for cooking, a celebration to mark the leaving of one of the group, the purchase of cricket bats, planning of trips to the beach and the possibility of purchasing a pool table.

The discussion about the pool table is a good example of the Common Third in action. The prohibitive cost meant the solution was to purchase materials and for a member of staff who was a carpenter to make this with four boys who volunteered to help. In this instance, staff share their skills; the boys learn new skills and relationships strengthened.

The preparation of food is another significant activity that maintains a connection with home, identity and culture. The boy’s request to make their own food, led to the purchase of equipment, herbs and spices. Cooking and sharing a meal has strengthened the relationship between the boy’s and staff team.

The care and respect for the boys is strong and mirrored in the way staff talk positively about the boys and seek to involve them in as many decisions as possible. This means accompanying staff to buy a cricket bat and determining the arrangements for trips to the beach. In turn, the boys are at ease with the staff, sharing smiles, gestures, and touch. In a film made by the boys to document their experience in the Safe Zone, activities took centre stage. In one scene, a boy preparing to travel to Germany, to join family, was visibly upset when saying his goodbyes. Another element of note was that the boys repeatedly used the term care to describe the staff’s attitude towards them.

Life beyond the Safe Zone is encouraged. All the young men attend Community schools and within the camp, there are additional lessons in Greek. Beyond the confines of the safe zone and the camp, other activities take place. This includes visiting a gym, computer classes and socialising with school friends on an evening or weekend.

The passions of individuals is taken into account, so that one young man who makes model houses and has an aptitude for design is found a place in a specialist art school, while another budding footballer is introduced to a local professional club. This all contributes to their identity as a young person rather than a refugee or asylum seeker.

These relationships create conditions for individual growth and possibilities beyond the Safe Zone that are the foundations of empowerment.

The plan now is to develop semi-independent provision for boys within local communities. This recognises that the legal and social challenges that boys face will be easier to overcome if they establish social networks within the community.

This approach is applicable to other settings in which young people are recipients of social care interventions.

The emphasis on the Common Third enables the boys to participate in the promotion of their own best interests. Therefore, while the activities are part of the everyday, they are not an end in themselves but a mechanism by which the boys strengthen relationships, develop their individual capabilities and identity and share connection with the group and community.

Thank you to the staff and boys in the Safe Zone for their warm welcome and permission to use these pictures.

References

Petrie, P., (2011) Interpersonal Communication: The Medium for Social Pedagogic Practice in C. Cameron and P. Moss (eds) Social Pedagogy and working with children and young people: Where care and education meet, London: Jessica Kingsley Publications.

UN General Assembly, Convention on the Rights of the Child, 20 November 1989, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1577, p. 3, available at: http://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html [accessed 22 July 2018].

Link to article