A kindred spirit to Youth Work?

by Jameel Hadi & Thure Johansen

“Children are not the people of tomorrow, but are people of today. They have a right to be taken seriously, and to be treated with tenderness and respect. They should be allowed to grow into whoever they were meant to be. ‘The unknown person’ inside of them is our hope for the future.” (Korczak 2007)

Janusz Korczak, 1878 – 1942

In this blog piece and those that follow, we would like discuss how the principle of the Common Third could help overcome the fragmentation that exists in youth services. We hope you are interested in what you read and feel like contributing to the debate, if so please join us for our immersion workshop on the Social Pedagogy & the Common Third on 12th December at NYA’s offices in Leicester.

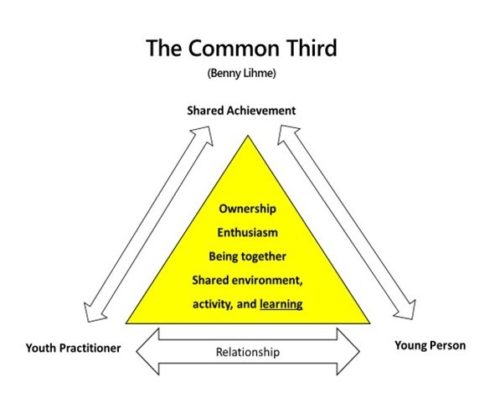

The Common Third can enrich and validate the role of activities and so reconnect with youth work traditions of association (http://infed.org/mobi/young-people-informal-education-and-association/). In Denmark the Common Third promotes ‘everyday activities’ and embodies social pedagogy’s commitment to learning and relationships.

Social Pedagogy

With its relationship-based and universal character, the Common Third is a key principle within the emerging UK social profession called Social Pedagogy, a firmly established and large social profession in many European countries and beyond. Up until now, most UK initiatives have focused on children looked after and family support, but to many the links and synergies with the Youth Work tradition have felt a potentially strong area to explore. In essence, Social pedagogy is values first practice (Petrie, 2011) that views people as rich in potential and promotes human equality and inclusion. Social pedagogy views people’s lifeworld (Grunwald & Thiersch, 2009) as a product of their interaction with their cultural and social environment, at a particular time.

Seen from this perspective, a young person is a unique individual whose behaviour and attitude is rooted within this lifeworld. The process of change is not separate from people’s activities and relationships. In this space, the person shapes their environment, and therefore their lifeworld, and transforms himself or herself through doing so.

The fast-changing terrain of Youth Work

The governments Civil Society strategy (https://nya.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/CSS-summary-youth-sector.pdf), provides an opportunity to reinvigorate youth work by re-establishing core values that promote strengths and relationships. This will feel like welcome and familiar territory for most people with some practice experience in the field. The Civil Society strategy reflects the fast-changing terrain of youth services and the central role of ‘positive activities’. These sort of activities form an integral part of the Friday night youth provision and the government’s flagship NCS programme that also aims to develop inclusion, leadership and social action.

The call to strengthen statutory youth work to address problems such as knife crime maintains the divide between targeted and universal approaches (https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jul/31/labour-vows-to-make-provision-of-youth-services-compulsory), and gives priority to ‘the problem’ rather the person and their social context and resources. This reflects the idea that young people are objects of concern, sites of human investment, or of risk: ‘future beings’ with developmental or behavioural challenges, rather than resourceful and active agents in their own lives. For example: child protection and risk dominate responses to Child Sexual Exploitation; legal status and social isolation shape the experience of young asylum seekers; and young people leaving care are isolated from relationships and networks of support. In these instances, targeted services can label, stigmatise and separate young people from their wider peer group. For example children in care are less likely to take part in formal adult led activities such as being members of a football team or drama club) and have less contact with their peer group as a result. This results in the absence of relationships and networks of support in the community, on leaving care (Hollingworth, 2012).

The Common Third – a relationship-based approach

Most professionals who work with young people recognize that the process, quality of relationships and experiences are more important than the outcome or task. The Common Third originates from Denmark, and has as its premise that a positive and authentic relationship is a powerful catalyst for human development rather than an ‘after-thought’ – a secondary priority to objectives defined at service level. Like Loris Malaguzzi’s Reggio Emilia approach, it considers the physical environment a third educator and something used with educational and relational intent (Hall and Horgan 2014).

An example could be a youth worker who agrees to take a newly formed group of young people out on a fishing boat, whether at their own expressed wish or as a creative suggestion. The intention would be to support relationship building and to nurture a positive culture with and within the group, whilst observing, then coming away with a greater understanding of individuals and of group dynamics, hidden talents and areas of confidence. As an experiential activity that offers everyone shared learning alongside and from each other, it may not specifically nail any targets set at service level. However, the tacit experience of many youth workers’ and social pedagogues’ will be that it is likely to be an ‘equaliser’ within a group and create a positive foundation from which further development can take place, using the same approach. The Common Third here points to the value of shared discovery and experiences.

Seen this way, the Common Third creates the conditions for the ‘unseen’ potential of which Januscz Korczak spoke. It creates future possibilities through serendipity and the incidental elements that arise in the course of activities. The ‘Third’ is an activity that is external to a problem or issue. Here the worker views themselves as in a relationship with the young person (s), creating a shared space through activities that values their contribution as equals.

The ‘being’ and ‘doing’ through every day activities creates self-efficacy, identity and self-esteem. These can be routine tasks such as preparing food, challenges, such as building, fixing or repairing things and creative or recreational activities. All these offer individuals and groups the potential for dialogue, meaning making, socialising and creating belonging. This equal relationship does not focus on the therapeutic or behavioural, but involves young people as partners who share their passions aspirations and capabilities.

A few examples (follow links for more information).

Common Third from Greece

The Common Third provides a holistic approach that promotes the voice and expressed needs of the young person. In Greece, it informs the approach to working with unaccompanied young people (https://medium.com/me/stats/post/a2f06d9b2759), by promoting their ‘best interests’ in contrast to procedural or legal criteria (UNCRC, 1989).

Common Third Examples from Denmark

In Copenhagen, the Municipality supports Idraetsprojeket (https://idraetsprojektet.kk.dk/an), an organisation that provides sport and recreational activities for ‘socially exposed’ young people. This connects ‘looked after’ young people with volunteer mentors and introduces them to group activities, involving young people who are not recipients of services. As Caecilie explains, “we take the point of departure as the child or adolescence’s wishes, competences and ideas in order to find the right activity – the Common Third. When arranging small-scale events, e.g., a football tournament or skate work shop; we involve the children or adolescents in all project phases on equal terms. In this way, the children/adolescents feel included, heard and useful. They do not show up for help but to do activities.” The elements of pleasure, trust, potentiality and belonging are key. These activities connect youngsters with their peer group and result in bridging and bonding capital for care leavers and other ‘socially exposed’ groups who are recipients of state services. This recognises that informal relationships are more important than the outcome based approach that dominates the looked after children system in England.

Changing the relationship between young people and professionals in this way means that the person is not a recipient of services but involved in all elements of the design and planning. Young people shape the rules, roles and expectations.

The Common Third reflects people’s intrinsic potential to learn, share and socialise. In an example from a Copenhagen area, the overriding aim of youth services is to overcome the ‘Berlin Wall’ of Albertslund , a geographical divide that separates the rich south from a poorer north. This recognises that inclusion requires a dialogue and people socialising together. Activities avoid the stigma resulting from targeted interventions because they create common ground where all are valued and contribute. Michael Husen the Danish philosopher explains how the activity undertaken creates the basis for the relationship. He uses the analogy of a party, which only exists in a true sense because the guests have previously shared activities (http://michaelhusen.dk/om-dette-site/).

Common Third Example from the UK (follow link for more information)

Here in the UK Participation Through Sport, 2003 to 2013(PTS) was a service that responded to young people’s wishes to participate through associational activities. This resulted in young people establishing community clubs where they led activities that reflected their priorities for socialising, safety and inclusion. This created a culture of volunteering and leadership, with youngsters, some as young as ten undertaking leadership awards and contributing to the community.

These community clubs connected youngsters who experience targeted and partial services with their wider peer groups. They included youngsters in care, refugees and asylum seekers, those with disabilities and a significant number who lack the financial support to access after school and holiday leisure activities. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mG6w_uuXqZ8). The above demonstrates the role of activity in enriching the life of all the participants. Inclusion is not simply about access and membership.

For example, youngsters who were problematic in other settings were valued and contributed within the environment created. Promoting participation through associational activities promotes the inclusion of young people not interested in consultative structures that mimic adult and professional forms. Here the participation in associational activities demonstrated that young people are resourceful and capable of contributing to communities as part of their self-development. The Civil Strategy is committed to young people’s participation in the commissioning, monitoring and evaluation of services and Initiatives. The examples provided show how the Common Third can create universal services that are inclusive and involve all young people as a unified group.

Taking stock and looking ahead

The Civil Society strategy reflects the changing terrain of youth services, with the introduction of new disciplines and organisations. The Common Third can help provide a coherent value based approach that re-establishes core youth work traditions of association and informal education. The establishment of the Social Pedagogy Professional Association (SPPA) opens up the possibility of a dialogue and partnership with professional youth work to embed ‘values as first practice’.

It is our hope that we may be able to take part in that discussion when we come to NYA in Leicester, as outlined above, and we would love to hear views and reflections from yourself if the above has started some thinking for you.

“The authors are indebted to Professor Pat Petrie a founding member of the Social Pedagogy Professional Association (SPPA) for her expertise, advice and help in editing this article”.

Additional Sources of Reading

Klaus Grunwald & Hans Thiersch (2009) The concept of the ‘lifeworld orientation’ for social work and social care, Journal of Social Work Practice, 23:2, 131-146, DOI: 10.1080/0265053090292364

Hall, Kathy / Horgan, Mary (2014) Loris Malaguzzi and the Reggio Emilia Experience, London, Bloomsbury Library of Educational Though

Korczak, J. (2007). Loving Every Child (Gift Edition). Algonquin Books: Workman.Langager, S. (2011). “If my friends are there, I’ll come too…” Social Pedagogy, Youth Clubs and Social Inclusion Processes. Chapter 11, Social Pedagogy for the Entire Lifespan, Volume 1, Edited, Kornbeck, J & Jensen, N, R. Bremen: EHV.

Petrie, P. (2011). Communication Skills for Working with Children and Young People (Third Edition). London: Jessica Kingsley.

UNCRC. (1989) https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_united_nations_convention_on_the_rights_of_the_child.pdf). Accessed 24/10/18.